The history of ventilation

Throughout evolution, humans have continued to create solutions to either adapt to their existing environments or make changes to improve them.

Animals are engineers

Nature is really surprising! Some animals are so creative and skilful that they even inspire engineers when designing and constructing.

Animals as environmental engineers

All living creatures use shelters to protect themselves from predators. And also to keep them safe inside their shelters.

- Beavers and their lodges are usually in upper areas of rivers and made of mud, stones and branches, with underground entrances.

- Spider species make different types of webs with varying functions, high strength and resistance, and are biodegradable.

Animals as ventilation engineers

Did you know that the first and most robust ventilation designs may probably be credited to the builders of the insect world?

- Bee colonies use wing power to regulate pollutants and airflows in their hives.

- Termites build tall mounds that are highly engineered to use wind-driven ventilation, airflow, and thermal mass to maintain comfort.

The firsts for improving the indoor climate

First for air quality

The earliest human-related indoor air quality problem may have been caused by the discovery of fire and the subsequent use of fires inside stone-age dwellings.

First for ventilative cooling

Ventilative cooling has long been used as a means to remove excess heat from buildings, bring in cooler air (where the outside air was cooler), and move the air fast enough to remove heat, cool the room, the person, and aid the body's natural cooling mechanisms.

First for building standards

In 1631, concluding that indoor conditions were causing health problems, King Charles I decreed that the ceilings in houses in England must be 10 feet or higher and that windows must be higher than their width to allow for natural ventilation. Note that 10 feet equals approximately 3 meters.

Ventus! Ventilatio! Ventilation!

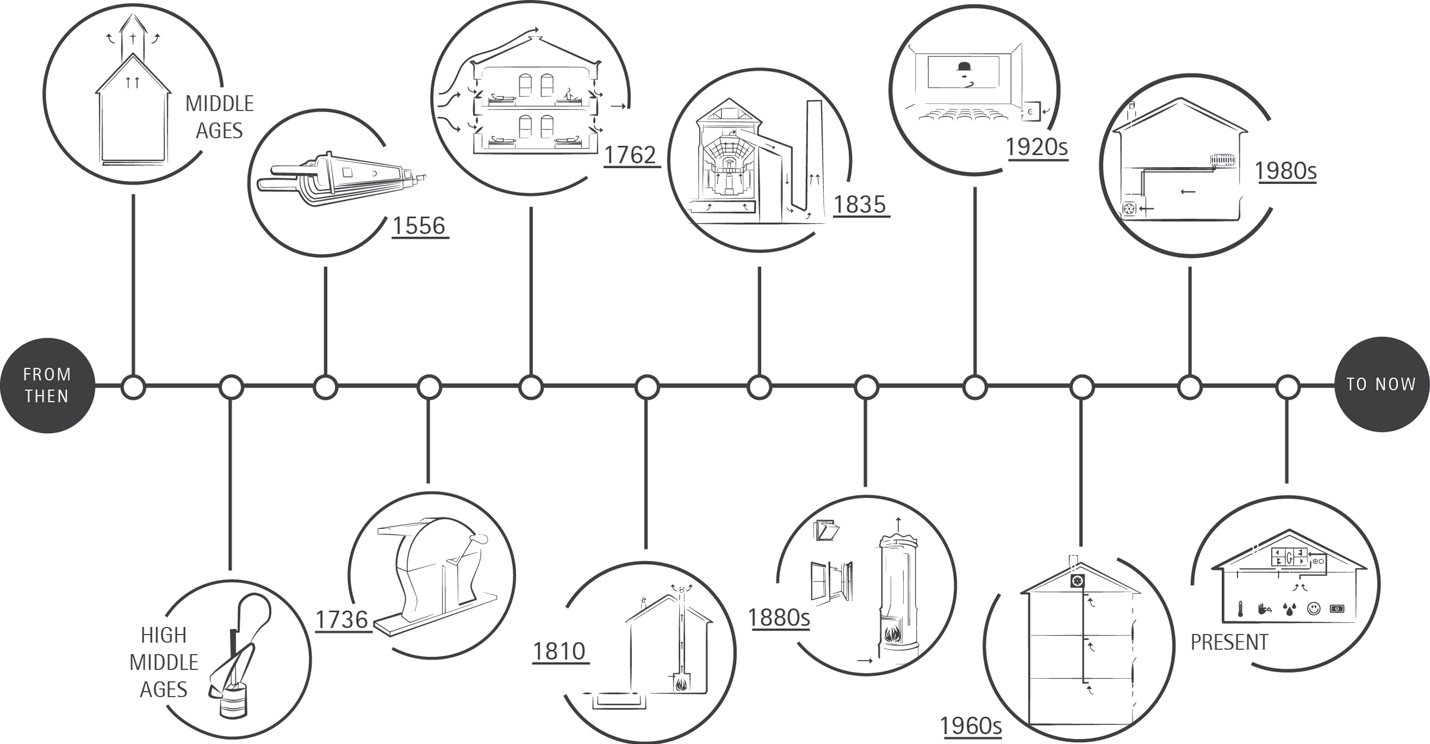

Some important milestones

Origin of the word ventilation

The word 'ventilation' comes from the Latin ventilatio, in turn from ventus meaning wind, which was described in 1660 as a process to 'replace poor air in an enclosed space with new and clean air'.

It was also used early on to mean 'breathing', i.e. the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in our lungs. The term was thus used to describe a process that was liberating, cleansing and necessary.

Want to read more about the history of ventilation?

Download our book, HISTORY of Ventilation Technology. History and knowledge form essential parts of our lives, and this book provides a short but comprehensive source for learning.

Download the book about History of Ventilation Technology

Important people in the history of ventilation

John Griscom (1774-1852)

A New York surgeon vividly described the need for fresh air and pointed out bedrooms and dormitories as the worst where: 'deficient ventilation ...(is) more fatal than all other causes put together'.

Max Joseph von Pettenkofer (1818-1901)

The first professor in hygiene in Munich — noted that the unpleasant sensations of stale air were not due merely to warmth or humidity or CO2 or oxygen deficiency, but rather to the presence of trace quantities of organic material exhaled from the skin and the lungs.

He stated that 'bad' indoor air did not necessarily make people sick but that such air weakened the human resistance against agents causing illness. Pettenkofer stated that air was not fit for breathing if the CO2 concentration (with people as the source) was above 1,000 ppm and that good indoor air in rooms where people stay for a long time should not exceed 700 ppm, to keep the people comfortable.

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Possibly the most complete overview of the relationship between indoor environment health was Florence Nightingale. She was a 'nurse & structural engineer'.

Nightingale wrote the first modern handbook for the nursing of sick 'Notes on Nursing, What It Is, and What It Is Not'. In her foreword she wrote that her book was meant as 'tips for women who are personally responsible for the health of others'.

Elias Heyman (1829–1889)

The first Swedish professor in hygiene at the Karolinska Institute conducted an extensive study in Stockholm of schools with different ventilation systems, including measurements of CO2.

In schools without any measures for ventilation, he measured concentrations of CO2 up to and over 5,000 ppm. In contrast, he typically measured maximum concentrations of between 1,500 and 3,000 ppm in schools with some ventilation.

Willis Carrier (1876–1950)

Known as the inventor (or father) of modern air-conditioning. Carrier designed his first system in 1902 to control temperature and humidity in a printing plant in Brooklyn (New York, USA).

Since then, air conditioning has been defined as a system with four basic functions: temperature regulation, humidity control, air circulation and/or ventilation and air purification (filtration).

Povl Ole Fanger (1934–2006)

A well-known and influential researcher in the 1960s working in the field of thermal comfort. Fanger focused on the relationship between the physical parameters of the environment, the physiological parameters of people and the perception of comfort expressed by people themselves.

In 1970, he published his dissertation 'Thermal Comfort', which defined a new discipline: the study of the condition of comfort and well-being in indoor environments. Compared to previous studies, the conceptual leap introduced by Fanger is the introduction of the judgment scale by people themselves.

Ventilation requirements within a historical context

Historically, humans have always focused on living in good conditions — where they feel safe and comfortable and can lead good and healthy lives.

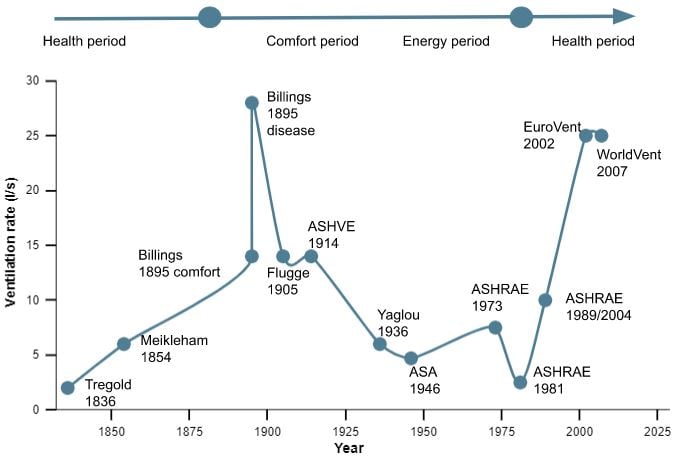

- The first quantitative ventilation recommendation was made by Tregold in 1836 and focussed primarily on the dilution of carbon dioxide. Over the next half century, the steady rise of ventilation recommendations was put in place due to the need to reduce contagions (mainly tuberculosis).

- After the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, improvements in hygiene reduced the need for high ventilation rates, and the rationale shifted towards comfort but not reducing exposure to toxic pollutants.

- The energy crisis in the last century shifted the focus even more on energy consumption — but only for a short period because of the emergence of building-related illnesses.

- In the 21st century, the focus has turned again towards health and even extended towards well-being and sustainability.

Throughout history, the ventilation rates have changed from around 2.5 to nearly 30 l/s per person — which is by a factor of 15.

Image source: Li, 2013.

Note: Image was adapted.

#history

More about history

If you are interested in more knowledge related to history, here are some interesting reading for you:

- Indoor climate — From past to present

- Indoor environmental quality (IEQ) — How it all began...

- Sick building syndrome (SBS) — Concept from 1983 by the WHO

- Historical development of the length of working days from the 1880s until today

- Air pollution — Past, present and future

- Daylight in history — From ancient Rome to Florence Nightingale

Read more from other sources

History is who we are and why we are the way we are.David McCullough, American historian