Indoor climate — from past to present

The history of indoor environment begins 1,5 million years ago when early humans began using campfires.

The backdrop to the indoor climate

Historically indoor air was considered harmful to human health; from ancient times by controlling and preventing the spread of disease, to the beginning of the hygienic revolution around the 1850s, and also when thermal comfort issues entered the discourse in the 1960s.

After the oil crisis in the 1970s, the main goal was to save energy, which, on the other hand, compromised the indoor environment conditions. At the end of the 20th century, new issues with sustainability, energy savings and renewable resources emerged.

Now in the 21st century, indoor environmental conditions, along with the productivity, health and well-being of building occupants, have become a dominant force.

The indoor climate is — and has for a very long time been — an essential element of architecture, building construction and technology.

From ancient times — Heating, hygiene and dampness

- For a long time, fire was used to provide heat inside cave dwellings, and later this source of heat was moved to buildings to provide a comfortable indoor environment (Swegon Air Academy, 2018).

- The Greeks and Romans were already aware of the adverse effects of polluted air in crowded cities and mines (Hippocrates, 460–377 BC).

- Living in buildings with dampness problems ('plague of leprosy') is dangerous to human health is already written in the Bible (Leviticus 14, 34–57).

1600-1800 — From health effects to human metabolism

- Later, connections were established between the health effects and working in heavily polluted environments (Ramazzini, 1633–1714), living in crowded cities such as London (Arbuthnot, 1667–1735), and the sad history of many young chimney sweeps (Pott, 1778).

- Poor air, poor ventilation and poor temperature were responsible for the spread of diseases, the death of slaves during transport overseas and the death of many prisoners, etc.

- Around 1800, knowledge focused on the understanding that breathing fresh air cools the heart, the discovery of oxygen, and understanding human metabolism, including the relationship between oxygen consumption and the release of carbon dioxide (CO2).

- In the following half of the 19th century, CO2 concentration was adopted as a measure of whether the air was fresh or stale.

1800-1900 — Fresh air, CO2 and ventilation

- In the 19th century, the nurse Florence Nightingale was a pioneer of fresh air, hygiene, sunlight and natural air ventilation, which all led to the improvement of health and well-being of patients in hospitals.

- J. von Pettenkofer's research focused on the fact that CO2 concentration (with a people as a source) could reach above 1,000 ppm (parts per million) and that good indoor air in rooms, where people stay for a long time, should not exceed 700 ppm to keep people comfortable (Pettenkofer, 1858).

- Heyman (1829–1889) studied various ventilation systems at schools in Stockholm. He would measure CO2 concentrations over 5,000 ppm in schools without ventilation and following this measured levels of 1,500 - 3,000 ppm in schools with some type of ventilation.

- In 1895, the ASHRAE recommended a minimum ventilation rate of 15 l/s per person.

1900-1960 — Comfort and ventilation rates

- In the first half of the 19th century, ventilation was primarily a matter of comfort, not health. Research was focused on: body odour in relation to ventilation rate; the effects of air recirculation; experiments with outdoor air supply (from 8 up to 15 l/s/p) and with (de)humidification, and the invention of air conditioning as a system with functions such as temperature control, humidity control, air circulation and/or ventilation, and air filtration.

- After the 1930s, not much scientific effort was devoted to ventilation and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ). However, some reflections were made about the perception of air quality, i.e. the differences between visitors and occupants.

1960-2000 — From IAQ to thermal comfort and the environment

- Around the 1960s, the focus changed completely from IAQ to the environment, as reports of health problems due to the polluted air emerged. This has led to the rise of environmental agencies and authorities focusing on safety and health at work, yet there was less focus on indoor air in homes.

- Between 1960 and 1980, the problems began in buildings with radon, dust mites, allergies, and sick building syndrome (SBS) and building-related illnesses (BRI).

- O. Fanger (1934–2006) focused his research on the impact of ventilation, indoor air humidity and thermal comfort, and on the sensory load of pollution sources other than people, such as building materials, carpets and computers.

Beginning of 21st century — IEQ, productivity, health and well-being

- The researchers concentrate on environmental and health issues linked with allergies, radon, particles, allergens, volatile/total/microbial organic compounds, etc.

- The focus is on health in the built environments with topics such as the influence of the indoor environment on productivity and supporting health, and well-being of occupants in all types of buildings — homes, offices, schools, etc.

- Interest has shifted from buildings being just energy-efficient, to being sustainable and providing a healthy environment — all at the same time. Worldwide, interest has emerged strongly in evaluating the sustainability of buildings with different certification schemes.

- We can see the explosive growth of awareness in related fields such as climate change, sustainability and renewables.

"If you go back 100 or 150 years, we had the same discussions around clean water, and now it is just accepted that everyone should have clean water. It should be the same thing with air. And we all breathe continuously, so we should be breathing good quality air."

— Catherine Noakes, Professor of Environmental Engineering for Buildings, University of Leeds, United Kingdom

Indoor climate is complex

Today, there is evergrowing interest in the indoor climate and its affects on people and their health & performance. In 2023, the World Health Organisation (WHO) had organized the first conference with the focus on the indoor air quality (IAQ).

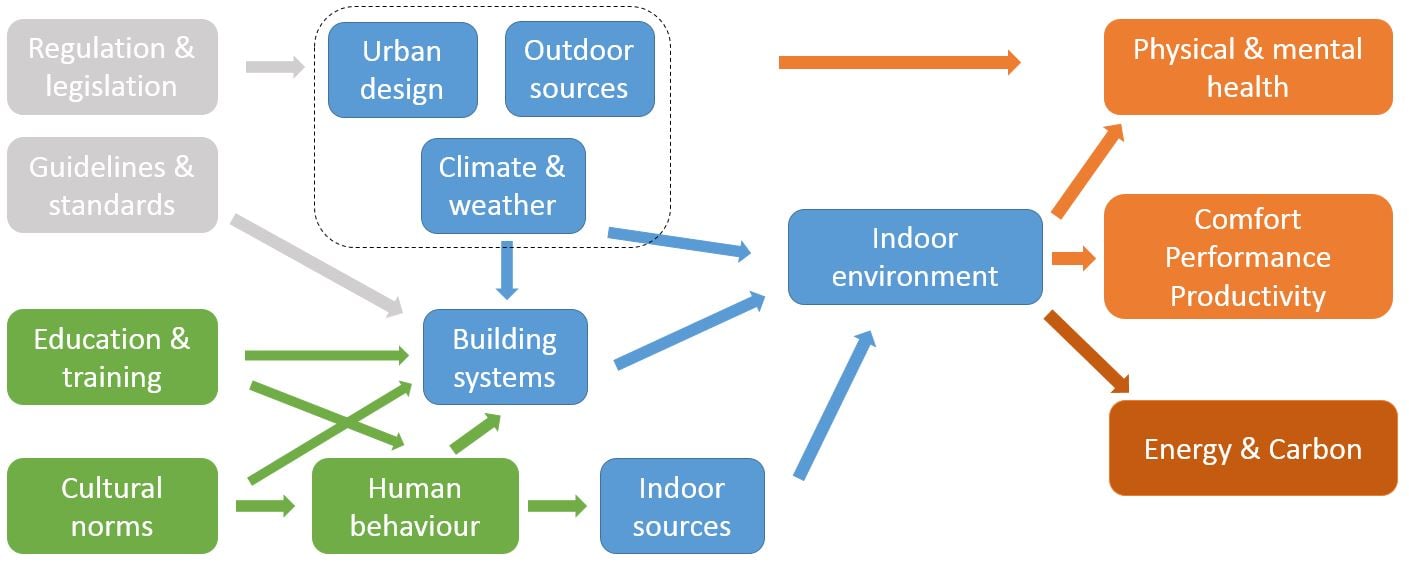

Still, there exists the image of 'indoor air is complex' and it illustrates the multiple different elements involved that have to be better understood to implement right strategies. There is a need to manage IAQ properly, and that can be done with more data gathering and to collect the data and insights for better decision-making.

The take-aways from the First WHO/Europe Indoor Air Conference 2023 are listed below:

- There is a paradigm chance in the indoor air quality including infection control.

- IAQ must not be compromised, similiarly to clean water and food quality.

- High indoor air quality = high outdoor air quality.

- We must act on existing evidence and we know what to do.

- IAQ rating is a must.

- Benefits of IAQ are high and must be considered.

- Health must be promoted in buildings.

Professor Cathrine Noakes, Professor of Environmental Engineering for Buildings, University of Leeds, United Kingdom, and being an expert on ventilation, building physics and airborne transmission, has presented the image below which summarize the image of 'indoor air is complex' at the First WHO/Europe Indoor Air Conference 2023.

Want to read more about the history of ventilation?

Download our book, HISTORY of Ventilation Technology. History and knowledge form essential parts of our lives and this book provides a short but comprehensive source for learning.

Download the book about History of Ventilation Technology

Read more from other sources

The more you know from the past, the better you are prepared for the future.Theodore Roosevelt